Creating Copies of Arrays & Objects

Array Copies

var squares = Array(9).fill(null); // Creates an array with 9 nulls

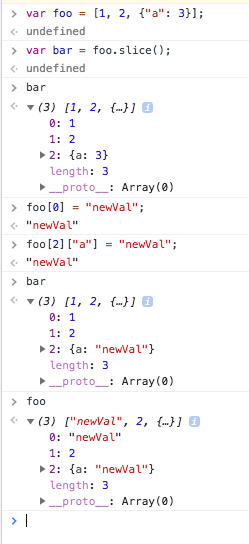

var copyOfSquares = squares.slice() // Creates a copy of squares. This comes with a pretty big caveat that it is in fact a SHALLOW copy. Meaning if the array contains elements which are either Arrays or Objects, those will be copied by reference. See example below

Object Copies

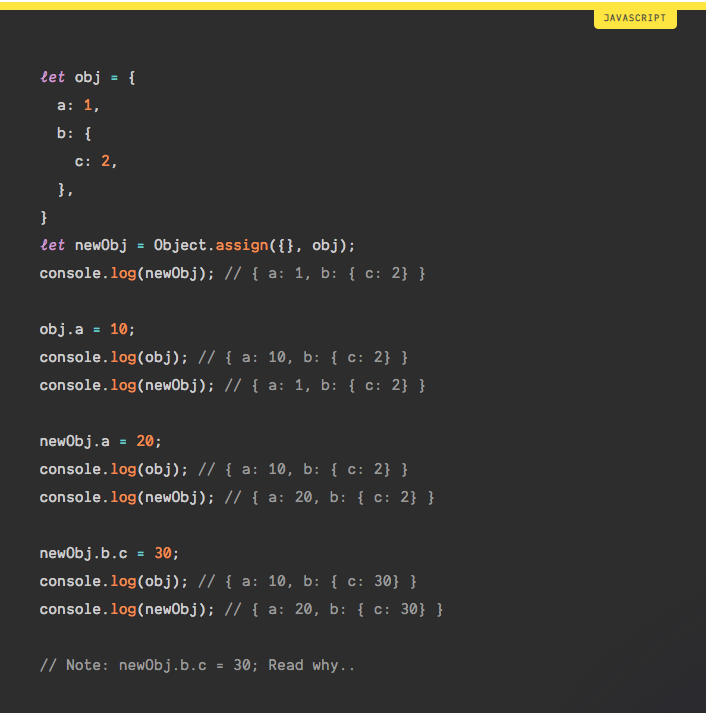

We have a couple different options here and the distinction between how they copy is super important. Some of the ways I've tried copying objects include:

// Option 1 - Object.assign

let newObject = Object.assign({}, sourceObjectOne, sourceObjectTwo);

// Option 2 - Spread Operator

let newObject = {...sourceObjectOne};

With these first two options they at first glance seem to copy by value and so changes to the source object won't affect the copy and vice versa. But any properties which are objects or arrays will be copied by reference. I'll post an example below.

// Option 3 - JSON parsing

let newOjbect = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(sourceOjbect));

// With this you will get a deep copy, meaning nothing is copied by reference but you'll run into issues with properties not being properly copied if they're functions of regex.

// Option 4 - A cloning library

var cloneDeep = require('lodash.clonedeep');

let newObject = cloneDeep(sourceObjectOne);

Either using a library or writing your own copy function is the only reliable way to create a deep copy of an object. I've started including the `clonedeep` method of lodash for this.

When to use Arrow Functions in ES6?

A while ago our team migrated all its code (a mid-sized AngularJS app) to JavaScript compiled using Babel. I'm now using the following rule of thumb for functions in ES6 and beyond:

- Use function in the global scope and for Object.prototype properties.

- Use class for object constructors.

- Use => everywhere else.

Why use arrow functions almost everywhere?

- Scope safety: When arrow functions are used consistently, everything is guaranteed to use the same thisObject as the root. If even a single standard function callback is mixed in with a bunch of arrow functions there's a chance the scope will become messed up.

- Compactness: Arrow functions are easier to read and write. (This may seem opinionated so I will give a few examples further on).

- Clarity: When almost everything is an arrow function, any regular function immediately sticks out for defining the scope. A developer can always look up the next-higher function statement to see what the

thisObjectis.

Why always use regular functions on the global scope or module scope?

- To indicate a function that should not access the thisObject.

- The window object (global scope) is best addressed explicitly.

- Many Object.prototype definitions live in the global scope (think String.prototype.truncate etc.) and those generally have to be of type function anyway. Consistently using function on the global scope helps avoid errors.

- Many functions in the global scope are object constructors for old-style class definitions.

- Functions can be named. This has two benefits: (1) It is less awkward to write

function foo(){}thanconst foo = () => {}— in particular outside other function calls. (2) The function name shows in stack traces. While it would be tedious to name every internal callback, naming all the public functions is probably a good idea. - Function declarations are hoisted, (meaning they can be accessed before they are declared), which is a useful attribute in a static utility function.

Object constructors

Attempting to instantiate an arrow function throws an exception:

var x = () => {};

new x(); // TypeError: x is not a constructor

One key advantage of functions over arrow functions is therefore that functions double as object constructors:

function Person(name) {

this.name = name;

}

However, the functionally identical2 ES Harmony draft class definition is almost as compact:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

}

I expect that use of the former notation will eventually be discouraged. The object constructor notation may still be used by some for simple anonymous object factories where objects are programmatically generated, but not for much else.

Where an object constructor is needed one should consider converting the function to a class as shown above. The syntax works with anonymous functions/classes as well.

Readability of arrow functions

The probably best argument for sticking to regular functions - scope safety be damned - would be that arrow functions are less readable than regular functions. If your code is not functional in the first place, then arrow functions may not seem necessary, and when arrow functions are not used consistently they look ugly.

ECMAScript has changed quite a bit since ECMAScript 5.1 gave us the functional Array.forEach, Array.map and all of these functional programming features that have us use functions where for-loops would have been used before. Asynchronous JavaScript has taken off quite a bit. ES6 will also ship a Promise object, which means even more anonymous functions. There is no going back for functional programming. In functional JavaScript, arrow functions are preferable over regular functions.

Take for instance this (particularly confusing) piece of code3:

function CommentController(articles) {

this.comments = [];

articles.getList()

.then(articles => Promise.all(articles.map(article => article.comments.getList())))

.then(commentLists => commentLists.reduce((a, b) => a.concat(b)));

.then(comments => {

this.comments = comments;

})

}

The same piece of code with regular functions:

function CommentController(articles) {

this.comments = [];

articles.getList()

.then(function (articles) {

return Promise.all(articles.map(function (article) {

return article.comments.getList();

}));

})

.then(function (commentLists) {

return commentLists.reduce(function (a, b) {

return a.concat(b);

});

})

.then(function (comments) {

this.comments = comments;

}.bind(this));

}

While any one of the arrow functions can be replaced by a standard function, there would be very little to gain from doing so. Which version is more readable? I would say the first one.

I think the question whether to use arrow functions or regular functions will become less relevant over time. Most functions will either become class methods, which make away with the function keyword, or they will become classes. Functions will remain in use for patching classes through the Object.prototype. In the mean time I suggest reserving the function keyword for anything that should really be a class method or a class.